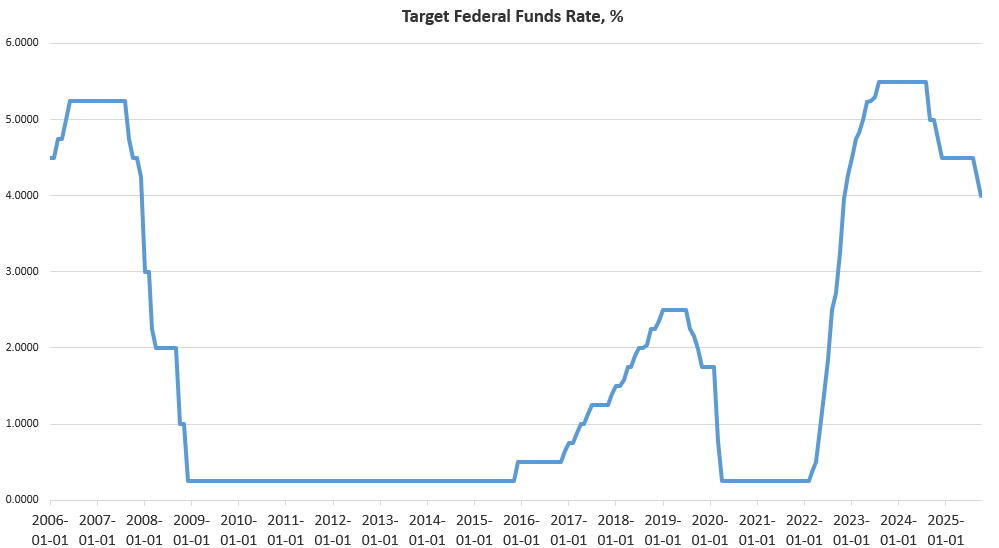

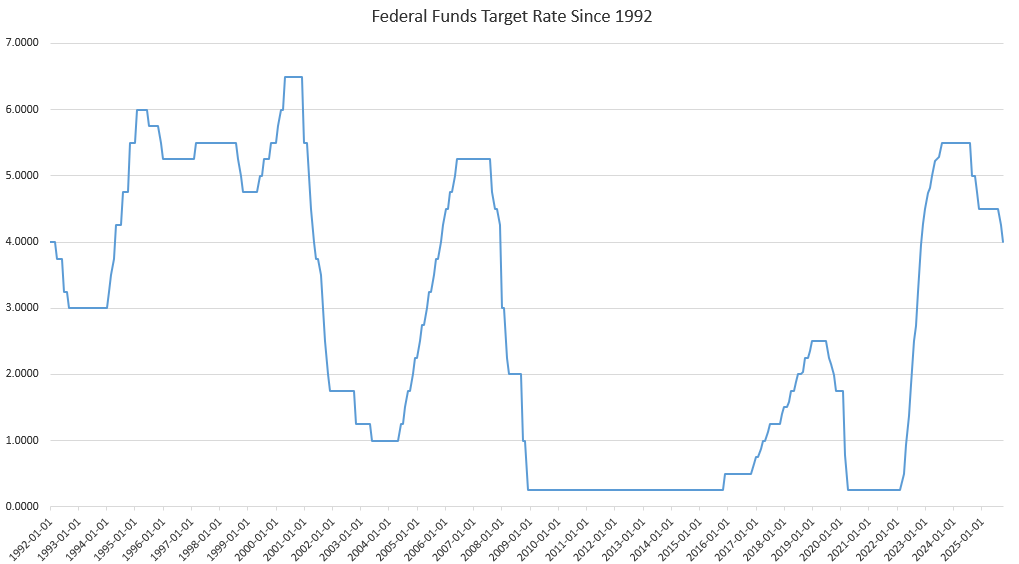

The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on Wednesday voted to again reduce the target policy interest rate by 25 basis points, down to an upper bound of 4.0 percent. The FOMC has now cut the policy rate (i.e., the federal funds rate) five times since September 2024, totaling a reduction in 150 basis points over 13 months.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell also announced on Wednesday that the Fed plans to end quantitative easing as of December 1. That is, the Fed will cease allowing reductions in its balance sheet and will switch to maintaining its balance sheet at current levels. Moreover, the Fed will reconfigure its balance sheet to increase its focus on Treasurys and reduce its holdings of mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed has embraced these further efforts at monetary easing even though official price-inflation rates continue to show that price inflation remains far from the Fed’s claimed two-percent goal. Apparently, the Fed has shifted its focus from price inflation to economic stimulus. After all, the FOMC’s policy changes, as well as Powell’s comments during the following press conference, paint a picture of a Fed that has all but completely abandoned any alleged commitment to a two-percent price-inflation target. The Fed is now preoccupied with the lackluster employment situation and providing ever more monetary stimulus.

Lowering the Target Interest Rate

With this new cut to the target policy interest rate, the FOMC continues its current cycle of monetary easing that has been in place since last fall. In spite of Fed claims that the US economy is robust, the 150-bp reduction is a clear sign that the Fed regards the US economy as incapable of standing on its own without continued monetary stimulus to maintain weakening bubble spending and investment.

In recent decades, a 150-bp-point drop in the target rate—with no intervening rate hikes— has always been followed by (or coincided with) a recession. This was certainly the case in 2001, 2008, and in 2020.

The Fed Ends Quantitative Tightening

As is expected, the Fed maintains that the economy is “expanding” in Wednesday’s FOMC statement, although the committee’s brief summary of economic conditions does admit of a slowing employment situation:

Available indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace. Job gains have slowed this year, and the unemployment rate has edged up but remained low through August; more recent indicators are consistent with these developments. Inflation has moved up since earlier in the year and remains somewhat elevated.

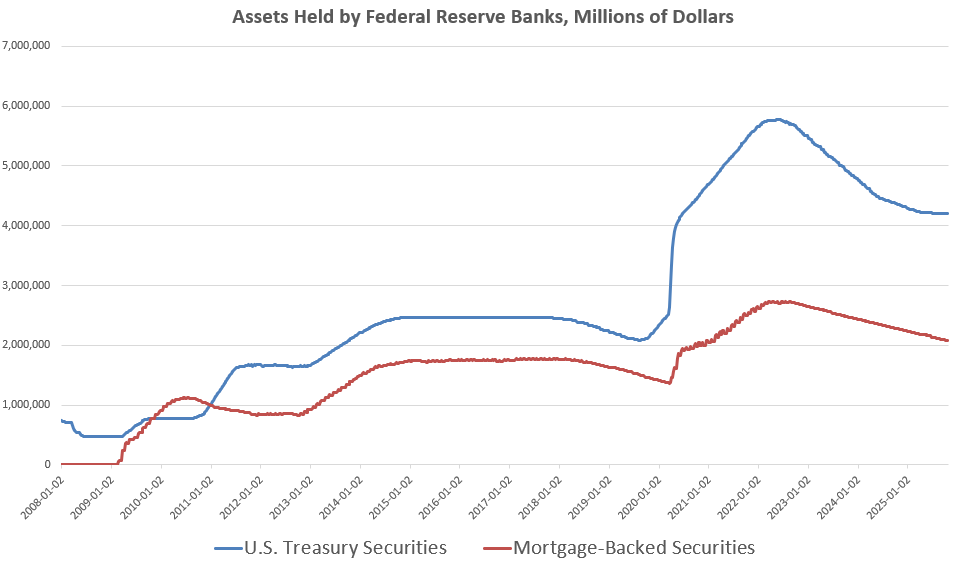

Further evidence of the Fed’s commitment to loosening economic conditions can be found in the FOMC’s new announcement that “quantitative tightening” will cease on December 1. In the current context “quantitative tightening” is the Fed’s slow but ongoing reduction in its balance sheet, where the Fed has amassed trillions of dollars in mortgage-backed securities and government Treasurys. Since 2008, the Fed has purchased these assets in an effort to reduce interest rates for Treasurys—by raising demand—and to create more liquidity for housing markets.

The total size of the portfolio peaked in mid 2022 at $5.7 trillion in Treasury debt and $2.7 trillion in mortgage securities. In recent years, however, the Fed has very slowly reduced the size of its portfolio, mostly by allowing assets to mature without replacing them. Since mid 2022, the portfolio has been reduced by a total of $2.2 trillion, with $1.5 trillion of that being Treasurys, and $651 billion being mortgage securities. This is not surprising because the Fed has always been committed to manufacturing demand for Treasurys to help reduce Treasury yields, and thus reduce interest paid on federal debt.

These assets were purchased with newly created dollars, so increases in the portfolio have resulted in adding trillions of dollars to the total money supply. Thus, the creation of the Fed’s massive asset hoard has long been an important component of quantitative easing. In contrast, when the Fed allows the size of the portfolio to shrink, this is a type of quantitative tightening, or “QT” and has a deflationary effect.

According to Powell, this will end in December at which time the Fed will presumably no longer allow the size of the portfolio to further decrease as assets mature and “roll off.” Instead, Powell noted the Fed will end QT by purchasing new assets to replace the older maturing assets. 1

Notably, Powell also stated that the Fed will work to increase the proportion of Treasurys in the portfolio, in relation to mortgage securities (i.e., agency securities). This is an extension of the Fed’s existing policy—begun earlier this year—of reducing its stock of mortgage securities at a faster rate than it has been reducing its stock of Treasurys.

Doubts About the Job Market

The FOMC statement maintains that the “unemployment rate has edged up but remained low,” but during the press conference, Powell clarified that “job creation ... is pretty close to zero” and so many FOMC members concluded “that it was appropriate for us to react by supporting demand with our rates.” Powell also admitted that the no hire, no fire economy persists, and he stated “available evidence suggests that both layoffs and hiring remain low, and that both households’ perceptions of job availability and firms’ perceptions of hiring difficulty continue to decline.” Prompted by questions, Powell admitted that there had a been a number of major layoff announcements earlier in the week and stated “we’re here to — by lowering rates at the margin that will support demand, and that will support more hiring. And that’s why we do it.”

Powell also stated that a large part of the employment story is a declining supply of labor, which has helped keep the labor situation seemingly stable. He noted that this is due to falling labor-force participation (for whatever reason) and also by the fact that “the supply of workers has dropped very, very sharply due to mainly immigration.” Powell doesn’t use the word “deportations” but that is clearly a factor in what he is describing here. In other words, there is very little hiring going on, but since the labor force has declined so much, a lack of hiring has prevented any significant surge in the unemployment rate.

After all, if the supply of labor falls at the same rate as the supply of jobs, the unemployment rate will not change. But, even here, Powell admits that “demand for workers has gone down a little more than supply.” This explains why the unemployment rate rose in August, even as the administration ramped up deportations. One can only guess what the unemployment rate would be of the supply of workers had continued to increase due to immigration or any other factor.

Has the Fed Given Up on the Two-Percent Price-Inflation Target?

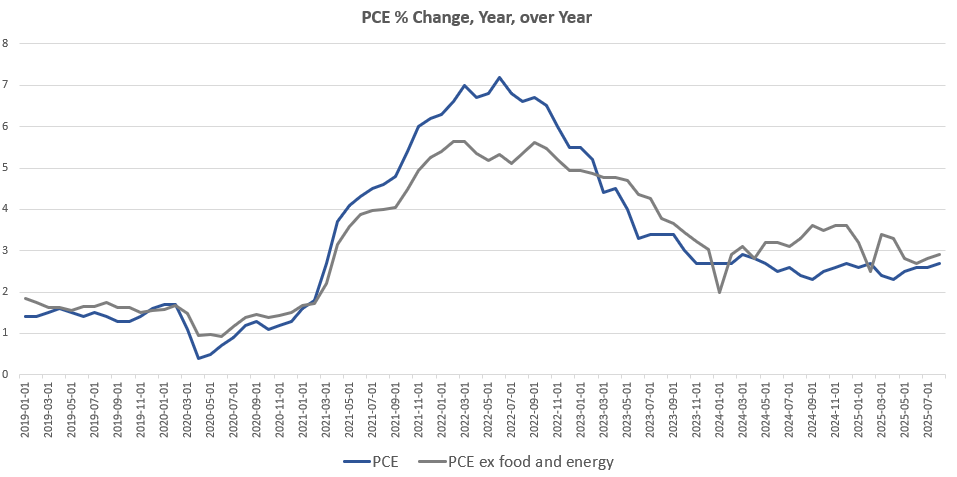

It is important to remember that all this talk of creating monetary stimulus in the face of a declining job market is happening while the official price-inflation number is nowhere near the Fed’s supposed two-percent target. Indeed, in the most recent CPI report, core price inflation was 3 percent, has been above three percent for three months. Core CPI year-over-year inflation has only dipped below 2 percent during three months of the past 53 months.

Last September, when the Fed began the current easing cycle, and lowered the target rate by 50 basis points, Powell claimed that price-inflation was rapidly returning to the two-percent target. Either his data was way off, or he was simply lying. Even measured by the PCE (the Fed’s preferred price-inflation measure), price-inflation is certainly not near two percent. The August PCE measure (the most recent available number) was up 2.7 percent, year over year, while the core PCE increase for August was 2.9 percent.

Yet, Powell has invented a way of waving this inconvenient data aside. In his remarks on Wednesday, Powell apparently invented a new inflation measure which can be described as ”price inflation minus the effects of tariffs.” Or, as Powell puts it:

inflation away from tariffs is actually not so far from our 2 percent goal. We estimate, people have different estimates of what that is, but it might be five or six tenths, and so if it’s 2.8, then core PCE, not including tariffs, might be 2.3 or 2.4, in that range, something like that. So that’s not so far from your goal.

Powell doesn’t offer any actual numbers or explanation of how he came up with this “price-inflation ex tariff” number. It’s apparently something the Fed is simply speculating about.

This new “measure” however, is nothing more than a political ploy used to explain away rising prices, so the Fed can claim that price inflation is really close to two percent, even if the federal government’s own official numbers say otherwise. The Fed might as well go back to claiming that price inflation is “transitory” because of “Putin’s price hike.”

Tariffs don’t cause inflation in the technical sense, of course, but in an environment of monetary inflation, tariffs do often contribute to upward pressure on prices of imports and import-dependent goods. So, what Powell is doing here is simply inventing a new number that excludes some higher prices from the CPI and PCE in order to create a narrative in which the Fed has steered price inflation back to two percent.

Once we look past this ruse, it’s likely we’re witnessing the Fed give up on its two-percent target in real time.

On the other hand, given the weakening job market, it could be that the Fed is betting on a worsening economy to get price-inflation back below two percent. A slowing economy, accompanied by a rapid slowdown in demand, would allow the Fed to continue to inflate the money supply without apparent inflation above the two percent target. This would only produce an illusion of success, of course, since monetary inflation combined with weakening demand simply robs ordinary people of the benefits of deflation—which are badly needed during times of economic bust—while still inflating new bubbles and creating new malinvestments.

- 1

At this time, the Fed has stated that it plans to use “proceeds” from maturing mortgage securities to purchase new Treasurys to prevent further reductions in the size of the portfolio. If the fed does stick to using only these proceeds to purchase new securities, then it is not actually increasing the money supply further, and the end of QT is not necessarily a new round of QE.